Introduction: Greatest Naval Clash

The Battle of Jutland, fought from May 31 to June 1, 1916, was the largest and most dramatic naval engagement of the First World War. Involving 250 warships and over 100,000 sailors, it marked the first—and only—clash between the British Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet. The battle unfolded in the icy waters of the North Sea, off the coast of Denmark’s Jutland Peninsula.

Initially perceived as a strategic blunder for the British, Jutland became the subject of controversy and public outcry. The Royal Navy, long hailed as the world’s greatest maritime force, suffered unexpectedly heavy losses in ships and sailors, leading many to question its competence and preparedness. Yet beneath the surface of disappointment lies a profound reality: Jutland was not the tactical victory Germany hoped for. It was a strategic triumph for Britain and the Allies, one that secured control of the seas and helped seal the fate of the German Empire.

A Battle Born of Blockade, Ambition

By 1916, Britain had imposed a devastating naval blockade on Germany, choking off critical supplies of food, fuel, and raw materials. Germany, a growing industrial power with limited access to overseas colonies, was highly dependent on imported goods. The blockade’s effects were crippling—not just economically, but socially and politically—causing widespread hardship, malnutrition, and unrest among the German population.

To break the blockade and regain initiative, the German Imperial Navy developed an ambitious plan. Admiral Reinhard Scheer, newly appointed commander of the High Seas Fleet, sought to isolate and destroy segments of the Royal Navy by using his faster, more modern battlecruisers under Vice-Admiral Franz von Hipper as bait. His goal was to lure the British out, inflict enough damage to weaken their naval superiority, and shift the balance of power in the North Sea.

However, British naval intelligence had a secret weapon—Room 40, a top-secret codebreaking unit within the Admiralty. They intercepted and deciphered German plans, allowing Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, commander of the Grand Fleet, and Vice-Admiral David Beatty, in charge of the Battlecruiser Fleet, to prepare an intercepting maneuver. The result was a fateful convergence of two massive fleets on the open seas.

The Clash Off the Coast of Denmark

The fleets met in the late afternoon on May 31, 1916, under grey skies and increasingly poor visibility. Initial contact was made between Beatty’s six battlecruisers and Hipper’s five, igniting a fierce duel. Within minutes, British ships began taking devastating hits. HMS Indefatigable exploded in a massive blast, sinking almost instantly and taking over a thousand crewmen with her. Soon after, HMS Queen Mary suffered a similar fate. These losses stunned observers and demoralized crews, raising alarms throughout the fleet.

Despite superior numbers, the British suffered from serious shortcomings. The early engagements revealed deep flaws in British naval doctrine, including poor ship design, lack of armor, and dangerous ammunition handling practices. Nonetheless, Beatty succeeded in drawing the Germans toward the main body of the Grand Fleet, where Admiral Jellicoe was poised for a major confrontation.

As night approached, Jellicoe executed a masterful tactical maneuver known as “crossing the T,” placing his battleships in an ideal position to unleash devastating broadsides against the oncoming German fleet. But poor visibility, evasive German tactics, and cautious decision-making limited the full impact of Jellicoe’s advantage.

The Hidden Causes of British Losses

Though the Royal Navy outnumbered the Germans in ships and guns, they lost more vessels—14 ships to Germany’s 11—and suffered over 6,000 casualties, more than twice the German toll. These figures shocked the British public and fueled political criticism. Yet recent research, including undersea exploration of the wrecks and analysis of wartime documents, offers deeper insight into why the Royal Navy suffered so heavily.

Outdated Tactical Doctrine: Many British admirals clung to 19th-century tactics despite the advent of modern naval technologies like radio communications, centralized fire control, and armor-piercing shells. Commanders lacked real-time situational awareness, leading to delays in action and missed opportunities to deliver decisive blows.

Design Flaws in British Ships: British battlecruisers were designed to prioritize speed over armor, a dangerous tradeoff. Their thin protection, especially around magazines and turrets, made them highly vulnerable to shellfire. When German shells hit, explosions often tore through entire decks, triggering catastrophic detonations.

Lax Ammunition Protocols: In pursuit of higher firing rates, British crews commonly stored extra powder charges outside of armored magazines. This reckless practice saved seconds but cost lives—once ignited by enemy shells, these charges amplified internal explosions, turning ships into floating infernos.

Meanwhile, German ships, though fewer in number, had superior armor distribution, compartmentalization, and disciplined handling of ammunition. Their heavy shells were also more effective at penetrating British defenses, contributing to the disparity in damage.

Tactical Stalemate, Strategic Victory

By the end of the night, the High Seas Fleet had managed to retreat under cover of darkness, avoiding total destruction. Superficially, it looked like a draw—or even a German win. However, this interpretation overlooks the strategic consequences of the battle.

After Jutland, the German navy never again seriously challenged the Royal Navy in surface combat. The High Seas Fleet remained largely confined to port for the remainder of the war, effectively ceding control of the North Sea to Britain. The Royal Navy, despite its losses, continued to enforce the blockade, tightening the economic noose around Germany.

Admiral Jellicoe was criticized by some for being overly cautious, but his restraint ensured that the British fleet—upon which the Empire’s security depended—remained intact. As Winston Churchill famously said, Jellicoe was “the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon.” He chose prudence over glory—and in doing so, helped preserve the path to eventual victory.

Naval Aftermath and Transformation

In the months following Jutland, both navies undertook massive overhauls. The Royal Navy reevaluated its doctrines, improved ship designs, and implemented stricter ammunition safety procedures. Lessons from Jutland directly influenced the construction of newer battleship classes such as the Revenge-class and later the Queen Elizabeth-class, which balanced firepower, armor, and speed more effectively.

For Germany, the battle marked a turning point. Having failed to destroy the Grand Fleet, they shifted focus toward unrestricted submarine warfare—a strategy that would provoke neutral nations, including the United States, and help tip the balance of the war.

Moreover, the psychological toll on the German fleet was immense. Morale declined steadily, and by late 1918, widespread mutinies among German sailors broke out, playing a key role in the collapse of the German monarchy and the onset of revolution.

Footage, Shipwrecks, Living Memory

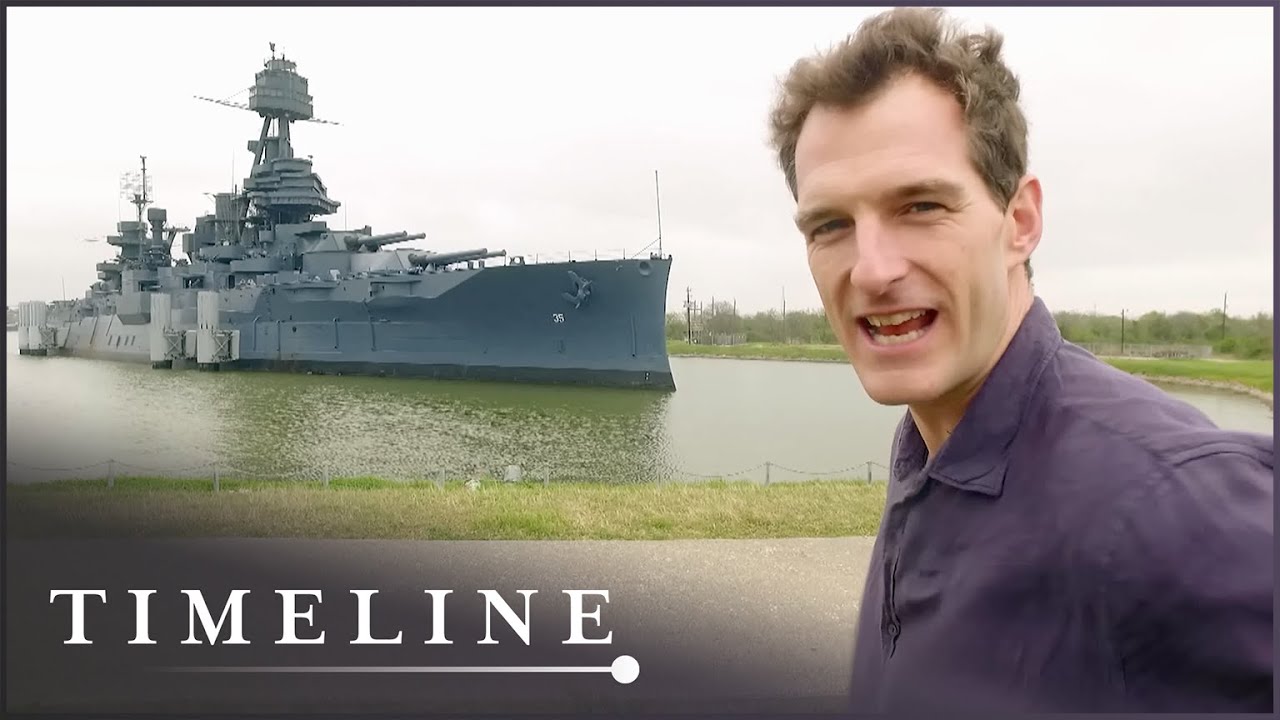

In the modern era, marine archaeologists have revisited the Jutland battlefield beneath the sea. The wrecks of HMS Invincible, Queen Mary, and several others lie undisturbed in deep water, serving as haunting underwater memorials. Remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and sonar scans have revealed twisted hulls, collapsed gun turrets, and the scars of explosions that ended thousands of lives in an instant.

Previously classified naval records, survivor memoirs, and rare film footage now allow historians to reconstruct the battle with unprecedented accuracy. This new understanding reframes Jutland not as a failure, but as a critical juncture in the war’s outcome—a pyrrhic tactical loss that delivered a strategic masterstroke.

Conclusion: Victory Beneath the Loss

The Battle of Jutland was not the resounding triumph the British people had hoped for, nor was it the crushing defeat the Germans needed. Instead, it was something subtler but far more significant: a quiet turning point in a long and brutal war.

It exposed weaknesses in British naval operations, leading to necessary reforms. It paralyzed the German fleet and maintained Allied dominance at sea. It showed that modern naval warfare required not just courage and firepower, but strategy, adaptation, and technological superiority.

In hindsight, Jutland was not just a clash of ships—it was a collision of eras, tactics, and empires. Though thousands died, their sacrifice helped preserve Allied maritime supremacy, eventually enabling the blockade and reinforcements that would win the war on land. It was, in every sense, the battle that secretly won World War I.