Introduction: Terror Behind the Legend

Before The Ghost and the Darkness became a chilling 1996 Hollywood thriller, the events that inspired it were far more horrifying and real. In 1898, during the construction of a railway bridge over the Tsavo River in what is now Kenya, two man-eating lions unleashed a reign of terror that halted British colonial progress. Over the course of several months, these lions stalked, dragged away, and devoured scores of Indian and African laborers—men who had been brought in by the British to lay down the iron spine of empire.

Estimates of the death toll vary, but official records placed the number at around 35, while local accounts suggest it may have been more than 100. For months, fear gripped the work camps. Entire groups of laborers abandoned the project in panic, and the British colonial government found itself in the grip of a public relations nightmare, as word of the attacks spread to London and India.

Who Was John Henry Patterson?

Colonel John Henry Patterson, an Anglo-Irish military engineer, was the man tasked with overseeing the railway bridge construction. Though he came to Africa as an engineer, he would be forced to become a hunter, protector, and ultimately, a hero. Patterson’s life was transformed by the nightmare at Tsavo.

A veteran of the British Army and a man of considerable experience, Patterson had expected the challenges of wildlife, disease, and climate. But nothing prepared him for lions who showed no fear of humans, attacked at night, and displayed behavior that baffled even seasoned hunters. Patterson began keeping a detailed journal of the killings and his own increasingly desperate attempts to stop them.

The Hunt Begins: A Test of Wits and Will

With his workers fleeing and the project in jeopardy, Patterson set traps, built protective enclosures, and waited night after night with his rifle—sometimes lying in trees or on makeshift platforms—hoping to ambush the predators. The lions, however, continued to evade capture, growing increasingly bold. They tore through tents, broke through thorn fences (bomas), and even dragged men from locked railway cars.

The first lion was finally shot in December 1898 after weeks of relentless tracking. Patterson described how the massive beast took multiple gunshots before succumbing. Three weeks later, the second lion fell to his bullets, following another grueling series of stakeouts. Patterson posed with the slain animals, documenting them for British newspapers and scientific journals.

Why Did the Lions Hunt Humans?

The Tsavo man-eaters were unlike typical lions in behavior and physiology. When scientists at the Field Museum in Chicago later examined the lions—whose skins Patterson donated—they found something unusual. One of the lions had a severe dental abscess, leading researchers to theorize that the pain might have made it difficult to hunt natural prey. But this doesn’t fully explain why the pair became persistent man-eaters.

Some scholars point to the proximity of a slave trade route and the possibility that the lions may have scavenged human remains long before the railway project began. Others highlight the disruption of their natural habitat and prey by British rail activity. Whatever the root causes, these lions adapted to an unnatural behavior with deadly results.

The Tsavo Legacy: Fear and Fascination

The horror of the Tsavo attacks left an indelible mark on both colonial history and popular imagination. Newspapers sensationalized the man-eaters, calling them “demons” and “phantoms,” while Patterson became a reluctant celebrity. His 1907 memoir, The Man-Eaters of Tsavo, became a bestseller and was studied by naturalists, military men, and big game hunters for decades.

The lions’ bodies were eventually stuffed and mounted. Today, they are on display at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, where they remain among the most visited exhibits—grim reminders of an episode that straddled myth and reality. Modern scientists continue to study the man-eaters, using isotopic analysis and forensic techniques to better understand how many humans they actually consumed.

Beyond the Jungle: Patterson’s Legacy

After Tsavo, Patterson’s career took unexpected turns. He served in World War I and later became a passionate Zionist, advocating for Jewish independence in Palestine. During the war, he commanded the Zion Mule Corps and later the Jewish Legion—precursors to the Israeli Defense Forces. Many Jewish leaders, including David Ben-Gurion, regarded him as a true friend of the Jewish people.

Despite his contributions, Patterson died in relative obscurity in California in 1947. It wasn’t until decades later that his remains were reburied in Israel with full military honors, a rare and symbolic act of recognition. Today, he’s remembered not just for his brush with death in Tsavo, but also as a forgotten ally in one of the world’s most enduring national movements.

Hollywood’s Version: Fact Vs Fiction

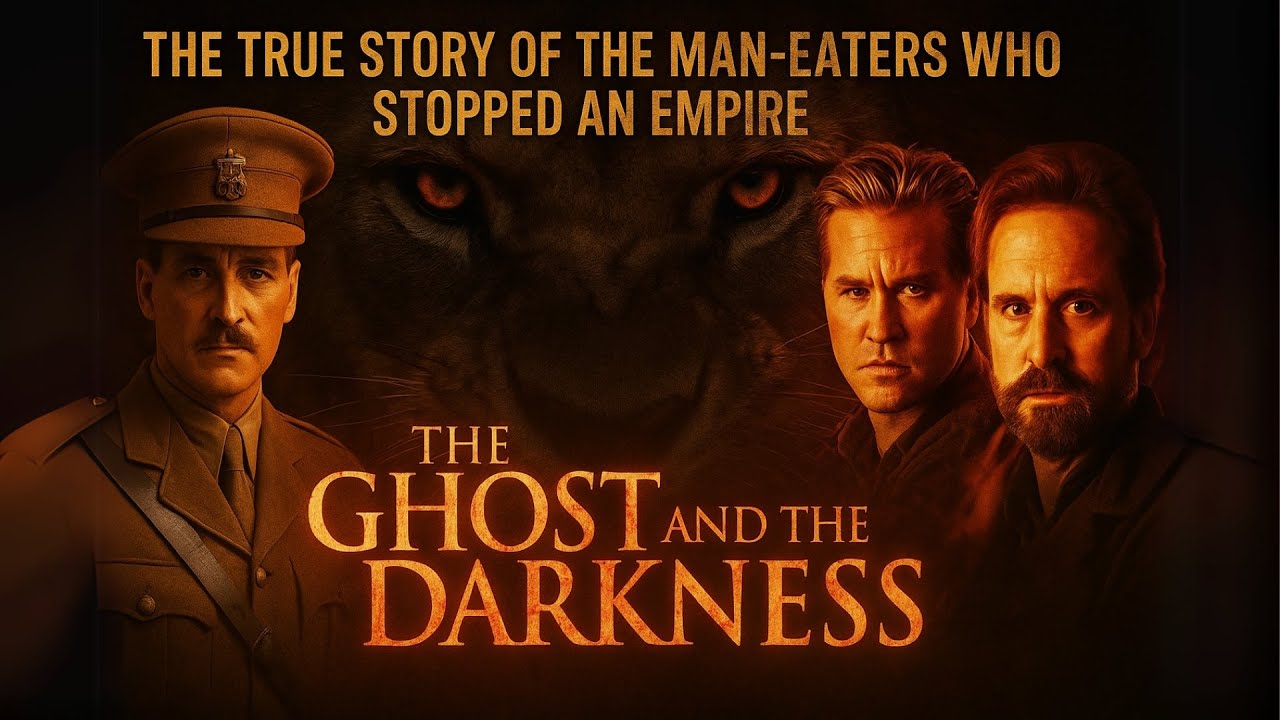

In 1996, the film The Ghost and the Darkness, starring Val Kilmer as Patterson and Michael Douglas as a fictional big-game hunter, brought the Tsavo story to modern audiences. While the film captures the terror and suspense of the lion attacks, it also takes significant liberties. Douglas’s character, for instance, is entirely fictional, added to boost drama and box office appeal.

Nonetheless, the film helped rekindle interest in Patterson’s story and the historical events behind it. For many, it was a first introduction to the dark chapter of colonial Africa and the psychological warfare between man and beast. The film may blur the line between myth and truth, but it undeniably honors the courage and resilience Patterson displayed.

Conclusion: When Nature Strikes Back

The story of the Tsavo man-eaters is more than a thrilling tale of survival. It’s a cautionary narrative about the limits of human dominance over nature, the vulnerabilities of colonial ambition, and the mysterious intelligence of predators. The lions weren’t just animals; they became symbols of nature’s ability to strike terror into even the most “civilized” of men.

Colonel Patterson’s bravery in the face of unimaginable horror endures as a compelling example of individual heroism. His legacy, though often overshadowed, speaks to the complex intersections of history, empire, and personal conviction. Today, the Tsavo lions remain frozen in time, not just in museum glass but in cultural memory—as grim totems of fear, resilience, and the haunting shadows where myth meets fact.